A Morte é um Muro ou uma Porta? Para Onde Apontam as Evidências Científicas?

- 2 dezembro 2025

- 14:00

- Autora: Taís Oliveira da Silva

A morte figura entre os temores mais profundos e as fascinações mais duradouras da humanidade, suscitando questões persistentes: O que é a morte? O que acontece após a morte? Esta reflexão baseia-se na indagação de Santos & Fenwick (2012): “A morte é um muro ou uma porta?” Os autores argumentam que a resposta a essa pergunta é crucial, pois pode exigir uma reconfiguração fundamental de nossa compreensão do cosmos e de nós mesmos, com implicações éticas e científicas de amplo alcance em todos os domínios do conhecimento.

Em diversas culturas, a morte é frequentemente compreendida por meio de lentes religiosas e espirituais moldadas por normas sociais. Historicamente, o morrer era um evento natural e íntimo — geralmente ocorrendo em casa, cercado por entes queridos e acompanhado por médicos à beira do leito (Figura 1). Com o tempo, essa experiência tornou-se cada vez mais medicalizada e institucionalizada, passando do ambiente doméstico para hospitais e sendo gerenciada principalmente por profissionais de saúde (Ariès, 2012).

Figura 1 – O Médico, Sir Luke Fildes

[1] O médico, pintado por Sr. Luke Fields em 1891, é uma representação comovente de um médico vitoriano que assiste a uma criança doente, destacando a compaixão, a dedicação profissional e o vínculo afetivo entre médico e paciente.

Embora os aspectos biológicos do processo de morrer sejam melhor compreendidos hoje, suas dimensões mentais, emocionais, psicossociais e — criticamente — espirituais permanecem amplamente negligenciadas. Essa lacuna é particularmente evidente considerando que mais de 56,8 milhões de pessoas no mundo necessitam de cuidados paliativos anualmente, incluindo 25,7 milhões em fase terminal, sendo 76% residentes em países de baixa e média renda, como o Brasil (Connor, 2020). Os cuidados paliativos visam explicitamente abordar o sofrimento físico, psicológico e espiritual (WHO, 2002), contudo, a espiritualidade continua recebendo atenção limitada na prática clínica e na pesquisa acadêmica (Balboni et al., 2022). Essa contradição torna-se ainda mais evidente diante da falta de compreensão e abordagem clínica das experiências subjetivas dos pacientes em fim da vida (Silva et al., 2024).

Evidências emergentes sugerem que as experiências de fim de vida (EFVs) são comuns e frequentemente impactam positivamente os pacientes (Silva et al., 2024). As EFVs englobam fenômenos subjetivos e transcendentes vivenciados por indivíduos em processo de morte, bem como eventos observáveis relatados por cuidadores e profissionais de saúde (Fenwick et al., 2010). Notavelmente, esses fenômenos têm sido documentados em diferentes culturas, períodos históricos e demográficos, independentemente de gênero, idade, condição médica, status socioeconômico, local de morte ou crenças religiosas/espirituais (Santos & Fenwick, 2012).

Embora observações científicas sobre EFVs remontem ao final do século XIX e início do século XX, o interesse empírico intensificou-se apenas recentemente (Silva et al., 2024). Apesar de ser um campo de pesquisa relativamente novo, estudos já foram realizados em todos os continentes, exceto África e Antártica. A maioria foi conduzida na América do Norte e Europa, ainda com amostras pequenas e relatos indiretos, em vez de testemunhos diretos de pacientes em fase final (Hession et al., 2023).

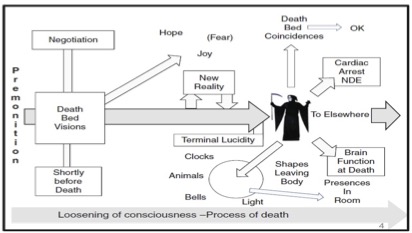

Estudos com profissionais de saúde categorizam as EFVs em dois tipos principais (Fenwick et al., 2010) — ver Figura 2:

EFVs Transpessoais: Experiências transcendentes que parecem antecipar a morte. Incluem sonhos e visões de fim de vida (SVFVs), transições para outras realidades, mudanças ambientais, coincidências no leito de morte, como relógios parando, luzes ou névoas ao redor do corpo, e comportamentos incomuns de animais no momento da morte.

EFVs de Significado Final: Experiências vívidas focadas no momento presente que levam os pacientes a resolver pendências, reconciliar-se com familaires afastados ou vivenciar lucidez terminal — um súbito retorno da clareza mental antes da morte.

Os SVFVs são as EFVs mais estudadas, frequentemente envolvendo entes queridos falecidos e temas de jornada ou transição (Silva et al., 2024). Essas experiências são geralmente reconfortantes para pacientes e familiares, com prevalência variando entre 50% e 88,1% em estudos de pacientes com avaliações frequentes próximas à morte (Silva et al., 2025).

Estudos quantitativos descrevem os SVFVs como vívidos, realistas e cada vez mais frequentes à medida que a morte se aproxima. São frequentemente significativos e reconfortantes (Kerr et al., 2014; Nyblom et al., 2021). Em um estudo longitudinal, 60,3% dos pacientes americanos consideraram seus SVFVs reconfortantes, especialmente quando envolviam entes queridos falecidos (Kerr et al., 2014).

SVFVs angustiantes, embora menos comuns, também são relatados e geralmente associados a traumas não resolvidos, sofrimento psicológico ou conflitos interpessoais (Nosek et al., 2015). Importante destacar que, mesmo quando angustiantes, essas experiências podem ter potencial terapêutico ao promover resolução emocional, perdão ou liberação de culpa (Kerr, 2021).

Em nosso estudo brasileiro, 34% de 85 pacientes terminais relataram EFVs, mais frequentemente durante o sono ou à noite, descritas como vívidas, realistas e vividamente lembradas. Essas experiências frequentemente envolveram entes queridos falecidos e variavam entre reconfortantes e angustiantes. Notavelmente, a proporção de EFVs angustiantes parece maior no Brasil (27%; Silva, 2025, submetido) e na Índia (84,2%; Dam, 2016) do que nos Estados Unidos (18,8%; Kerr et al., 2014). Essas diferenças podem refletir variações metodológicas (por exemplo, duração do acompanhamento, frequência das entrevistas, pergunta de triagem) e fatores socioculturais mais amplos, como crenças sobre a morte, conflitos emocionais não resolvidos e desigualdades na qualidade dos cuidados de fim de vida (EIU, 2015; Renz et al., 2018).

Apesar dos altos níveis de religiosidade/espiritualidade e crença na vida após a morte entre brasileiros e nessa amostra de pacientes (Monteiro de Barros et al., 2022), esses fatores não explicaram completamente como as EFVs foram interpretadas, sugerindo a influência de estruturas psicossociais e culturais mais amplas. Pesquisas mostram que as interpretações individuais de experiências transcendentes moldam fortemente os resultados emocionais, com avaliações negativas associadas ao sofrimento (Maraldi et al., 2024). A consistência transcultural das características das EFVs — vivacidade, realismo e significado emocional — indica que esses fenômenos podem ser intrínsecos ao processo de morrer, embora influenciados por sistemas culturais de significado. Pesquisas transculturais adicionais são essenciais para compreender essas dinâmicas e aprimorar os cuidados de fim de vida.

Coletivamente, as evidências científicas atuais desafiam a visão do morrer como um declínio puramente passivo, sugerindo que os pacientes podem permanecer espiritualmente e psicologicamente ativos, continuando seu desenvolvimento interior apesar da deterioração física (Kerr, 2021). Fatores socioculturais parecem desempenhar papel crítico na interpretação e impacto emocional dessas experiências.

Quanto às hipóteses explicativas, modelos biológicos frequentemente classificam os SVFVs como alucinações ou delírios decorrentes de medicação ou instabilidade clínica. No entanto, diferentemente do delirium — definido basicamente por cognição flutuante e atenção prejudicada (Maldonado, 2018) — os SVFVs ocorrem frequentemente em pacientes conscientes, orientados e capazes de recordar os eventos com clareza. Eles também diferem das alucinações típicas em sua clareza, organização e ressonância emocional (Kerr et al., 2014). Estudos não encontraram associação significativa entre uso de opioides e os SVFVs (Osis & Haraldsson, 1977; Muthumana et al., 2011), e mesmo na presença de delirium, essas experiências frequentemente mantêm qualidades distintas e significativas (Kerr et al., 2021).

Interpretações psicológicas propõem que estresse severo e isolamento podem levar pacientes em fim de vida a fazer atribuições errôneas as suas imagens internas como forma de enfrentamento ou “reação esquizóide” (Osis & Haraldsson, 1977). Contudo, os pacientes frequentemente descrevem os SVFVs como “mais reais que a realidade”, associadas à aceitação, e não à negação da morte. Relatos de encontros com parentes falecidos e casos “Peak in Darien” — nos quais pacientes percebem indivíduos recém-falecidos cuja morte era desconhecida — desafiam explicações puramente defensivas ou baseadas em expectativas (Greyson, 2010).

Interpretações espirituais sugerem que os SVFVs podem refletir encontros genuínos, indicando uma possível dissociação temporária entre mente e cérebro próximo à morte (Moreira-Almeida et al., 2022). Embora as correlações mente–cérebro estejam bem estabelecidas, a fenomenologia dos SVFVs e de outras experiências não ordinárias, como lucidez terminal e experiências de quase morte, evidenciam limitações nos modelos neurobiológicos atuais.

A questão sobre se a morte representa um fim definitivo (muro) ou uma transição significativa (porta) permanece sem resposta. Independentemente de sua natureza última, os SVFVs frequentemente proporcionam conforto e apoiam a adaptação psicológica no fim da vida. Os profissionais de saúde têm, portanto, a responsabilidade ética de reconhecer e validar essas experiências dentro de um cuidado compassivo.

À medida que o entendimento científico sobre o processo de morrer avança, as dimensões psicológicas e espirituais reveladas pelas EFVs — especialmente pelos SVFVs — apontam para o morrer como um processo de transição potencialmente significativo, e não mera cessação. Pesquisas longitudinais mais rigorosas são necessárias para explorar com profundidade esses fenômenos e apoiar uma abordagem mais holística aos cuidados de fim de vida.

Se você atua em cuidados paliativos ou em hospice e deseja aprofundar-se no manejo clínico dos sonhos e visões de fim de vida (ELDVs, na sigla em inglês), convidamos você a participar de um treinamento on-line interativo. Acesse o treinamento aqui: https://hospice-buffalo-9171.reach360.com/share/course/31c5bfbd-d9cb-4292-ba14-30b378d2bde7

Referências

- ARIÉS, P. História da morte no Ocidente: da Idade Média aos nossos dias. Tradução: Priscila Viana de Siqueira. Edição especial. Rio de Janeiro: Nova Fronteira, 2012.

- BALBONI, T. A. et al. Spirituality in serious illness and health. JAMA, v. 328, n. 2, p. 184-197, 2022. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2022.11086.

- CONNOR, S. Global Atlas of Palliative Care. 2nd ed. 2020.

- DAM, A. K. Significance of end-of-life dreams and visions experienced by the terminally ill in rural and urban India. Indian Journal of Palliative Care, v. 22, n. 2, p. 130-134, 2016. DOI: 10.4103/0973-1075.179600.

- DEPNER, R. M. et al. Expanding the understanding of content of end-of-life dreams and visions: a consensual qualitative research analysis. Palliative Medicine Reports, v. 1, n. 1, p. 103-110, 2020. DOI: 10.1089/pmr.2020.0037.

- ECONOMIST INTELLIGENCE UNIT. The 2015 Quality of Death Index: ranking palliative care across the world. New York: EIU, 2015.

- FENWICK, P.; LOVELACE, H.; BRAYNE, S. Comfort for the dying: five year retrospective and one year prospective studies of end of life experiences. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, v. 51, n. 2, p. 173-179, 2010. DOI: 10.1016/j.archger.2009.10.004.

- GREYSON, B. Seeing dead people not known to have died: “Peak in Darien” experiences. Anthropology and Humanism, v. 35, n. 2, p. 159-171, 2010. DOI: 10.1111/j.1548-1409.2010.01064.x.

- HESSION, A. et al. End-of-life dreams and visions: a systematic integrative review. Palliative & Supportive Care, v. 21, n. 2, p. 337-346, 2023. DOI: 10.1017/S1478951522000876.

- KERR, C. W. et al. End-of-life dreams and visions: a longitudinal study of hospice patients’ experiences. Journal of Palliative Medicine, v. 17, n. 3, p. 296-303, 2014. DOI: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0371.

- KERR, C. Experiences of the dying: evidence of survival of human consciousness. Consciousness Bigelow Institute, 2021. Disponível em: https://www.bigelowinstitute.org/Winning_Essays/5_Christopher_Kerr.pdf. Acesso em: 15/10/2025.

- MALDONADO, J. R. Delirium pathophysiology: an updated hypothesis of the etiology of acute brain failure. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, v. 33, n. 11, p. 1428-1457, 2018. DOI: 10.1002/gps.4823.

- MARALDI, E. O. et al. Nonordinary experiences, well-being and mental health: a systematic review of the evidence and recommendations for future research. Journal of Religion and Health, v. 63, n. 1, p. 410-444, 2024. DOI: 10.1007/s10943-023-01875-8.

- MONTEIRO DE BARROS, M. C. et al. Prevalence of spiritual and religious experiences in the general population: a Brazilian nationwide study. Transcultural Psychiatry, 6 Apr. 2022. DOI: 10.1177/13634615221088701.

- MOREIRA-ALMEIDA, A.; COSTA, M.; COELHO, H. Science of life after death. Switzerland AG: Springer Nature, 2022.

- MUTHUMANA, S. et al. Deathbed visions from India: a study of family observations in northern Kerala. Omega, v. 62, n. 2, p. 97-109, 2010. DOI: 10.2190/om.62.2.a.

- NOSEK, C. L. et al. End-of-life dreams and visions: a qualitative perspective from hospice patients. American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Medicine, v. 32, n. 3, p. 269-274, 2015. DOI: 10.1177/1049909113517291.

- NYBLOM, S. et al. End-of-life experiences (ELEs) of spiritual nature are reported directly by patients receiving palliative care in a highly secular country: a qualitative study. American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Medicine, v. 38, n. 9, p. 1106-1111, 2021. DOI: 10.1177/1049909120969133.

- OSIS, K.; HARALDSSON, E. Deathbed observations by physicians and nurses: a cross-cultural survey. Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, v. 71, n. 3, p. 237-259, 1977.

- RENZ, M. et al. Fear, pain, denial, and spiritual experiences in dying processes. American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Medicine, v. 35, n. 3, p. 478-491, 2018. DOI: 10.1177/1049909117725271.

- SANTOS, F.; FENWICK, P. Death, end of life experiences, and their theoretical and clinical implications for the mind–brain relationship. In: MOREIRA-ALMEIDA, A.; SANTANA SANTOS, F. (org.). Exploring frontiers of the mind-brain relationship. New York: Springer, 2012. p. 165-189. (Mindfulness in Behavioral Health).

- SILVA, T. O.; LEVY, K.; KERR, C. W. End-of-life experiences in patients: a scoping review of types, characteristics, and implications for the mind-brain relationship. International Review of Psychiatry, v. 37, n. 2, p. 142-156, 2025. DOI: 10.1080/09540261.2025.2503726.

- SILVA, T. O.; RIBEIRO, H. G.; MOREIRA-ALMEIDA, A. End-of-life experiences in the dying process: scoping and mixed-methods systematic review. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care, v. 13, e624-e640, 2024. DOI: 10.1136/spcare-2022-004055.

- WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION. National cancer control programmes: policies and managerial guidelines. 2nd ed. Geneva: WHO, 2002.

“Is Death a Wall or a Door?” Where Does Scientific Evidence Point?

Death is among humanity’s deepest fears and most enduring fascinations, prompting persistent questions: What is death? What happens after death? This reflection draws on Santos and Fenwick’s (2012) inquiry, “Is death a wall or a door?” The authors argue that the answer is pivotal, as it may require a fundamental reconfiguration of our understanding of the cosmos and of ourselves, with far-reaching ethical and scientific implications across all domains of knowledge.

Across cultures, death is often understood through religious and spiritual lenses shaped by societal norms. Historically, dying was a natural, intimate event – typically occurring at home, surrounded by loved ones and attended by bedside physicians (Figure 1). Over time, however, this experience has become increasingly medicalized and institutionalized, shifting from the home to hospitals and managed primarily by healthcare professionals (Ariès, 2012).

While the biological aspects of dying are now better understood, its mental, emotional, psychosocial, and – critically – spiritual dimensions remain largely neglected. This gap is particularly striking given that more than 56.8 million people worldwide require palliative care annually, including 25.7 million nearing the end of life, with 76% living in low- and middle-income countries such as Brazil (Connor, 2020). Palliative care explicitly aims to address physical, psychological, and spiritual suffering (WHO, 2002), yet spirituality continues to receive limited attention in clinical practice and academic research (Balboni et al., 2022). This contradiction becomes even more evident when considering the lack of understanding and clinical engagement with patients’ inner experiences at the end of life (Silva et al., 2024).

Emerging evidence suggests that end-of-life experiences (ELEs) are common and often positively impact the dying (Silva et al., 2024). ELEs encompass subjective and transcendent phenomena experienced by dying individuals and observable deathbed events reported by caregivers and clinicians (Fenwick et al., 2010). Notably, these phenomena have been documented across cultures, historical periods, and demographics, regardless of gender, age, socioeconomic status, medical condition, place of death or religious/spiritual beliefs (Santos & Fenwick, 2012).

Although scientific ELEs date back to the late 19th and early 20th centuries, empirical interest has only recently intensified (Silva et al., 2024). Despite being a relatively new research focus, studies have emerged across all continents except Africa and Antarctica. Most have been conducted in North America and Europe, often relying on small samples and second-hand accounts rather than direct reports from dying patients (Hession et al., 2023).

Clinician studies categorize ELEs into two main types (Fenwick et al., 2010) – See Figure 2:

- Transpersonal ELEs: Transcendent experiences that seem to foreshadow death. These include end-of-life dreams and visions (ELDVs), transitions to other realities, environmental changes, deathbed coincidences, such as clocks stopping, lights or mists around the body, and unusual animal behavior at the time of death.

- Final Meaning ELEs: These are present-focused, involving vivid experiences that prompt patients to resolve unfinished business, reconcile relationships, or experience terminal lucidity – a sudden return of mental clarity before death.

ELDVs are the most extensively studied ELEs often involving deceased loved ones and themes of journey or transition (Silva et al., 2024). These experiences are typically comforting for patients and families, with prevalence ranging from 50% to 88.1% in patient’s studies with frequent assessments near death (Silva et al., 2025).

Quantitative studies describe ELDVs as vivid, realistic, and increasingly frequent as death approaches. They are often personally meaningful and comforting (Kerr et al., 2014; Nyblom et al., 2021). In one longitudinal study, 60.3% of American patients found their ELDVs comforting, especially when deceased loved ones appeared (Kerr et al., 2014).

Distressing ELDVs, though less common, are also reported and often linked to unresolved trauma, psychological distress, or interpersonal conflict (Nosek et al., 2015). Importantly, even when distressing, these experiences may still hold therapeutic potential by promoting emotional resolution, forgiveness, or the release of guilt (Kerr, 2021).

In our Brazilian study, 34% of 85 terminally ill patients reported ELEs, most commonly during sleep or at night, and described them as vivid, realistic, and vividly remembered. These experiences frequently involved deceased loved ones and ranged from comforting to distressing. Notably, the proportion of distressing ELEs appears higher in Brazil (27%; Silva, 2025, submitted) and India (84.2%; Dam, 2016) than in the United States (18.8%; Kerr et al., 2014). Such differences may reflect methodological variation (e.g., follow-up duration, interview frequency, screening question) and broader sociocultural factors, including cultural beliefs about death, unresolved emotional conflicts, and disparities in the quality of end-of-life care (EIU, 2015; Renz et al., 2018).

Despite the high levels of religiosity/spirituality, and belief in life after death among Brazilians and within this patient sample (Monteiro de Barros et al., 2022), these factors alone did not fully account for how ELEs were interpreted, suggesting the influence of broader psychosocial and cultural frameworks. Research shows that individuals’ interpretations of transcendent experiences strongly shape emotional outcomes, with negative appraisals linked to distress (Maraldi et al., 2024). The cross-cultural consistency of ELE features—vividness, realism, and emotional significance—indicates that these phenomena may be intrinsic to the dying process, while still shaped by cultural meaning systems. Further cross-cultural research remains essential to understand these dynamics and improve end-of-life care.

Collectively, current scientific evidence challenges the view of dying as purely a passive decline,suggesting instead that patients may remain spiritually and psychologically active, continuing inner development despite physical deterioration (Kerr, 2021). Sociocultural factors appear central to how these experiences are interpreted and emotionally processed.

Regarding explanatory hypotheses, biological models often classify ELDVs as hallucinations or delirium resulting from medication or clinical instability. Yet, unlike delirium—defined by fluctuating cognition and impaired attention (Maldonado, 2018) – ELDVs frequently occur in patients who remain conscious, oriented, and able to recall the events clearly. They also differ from typical hallucinations in their clarity, organization, and emotional resonance (Kerr et al., 2014). Studies have found no significant association between opioid use and ELDVs (Osis & Haraldsson, 1977; Muthumana et al., 2011), and even in the presence of delirium, these experiences often retain distinct and meaningful qualities (Kerr et al., 2021).

Psychological interpretations propose that severe stress and isolation may lead dying patients to misattribute internal imagery as a form of coping or “schizoid reaction” (Osis & Haraldsson, 1977). However, patients frequently describe ELDVs as “more real than reality,” associated with acceptance rather than avoidance of death. Reports of encounters with deceased relatives and “Peak in Darien” cases—where patients perceive the recently deceased unknown to them—challenge purely defensive or expectation-based explanations (Greyson, 2010).

Spiritual interpretations propose that ELDVs may reflect genuine encounters, suggesting a temporary decoupling of mind and brain near death (Moreira-Almeida et al., 2022). Although mind–brain correlations are well established, the phenomenology of ELDVs and cases of others non-ordinary experiences, such as terminal lucidity and near-death experiences highlight limitations in current neurobiological models.

The question of whether death represents a definitive end (wall) or a meaningful transition (door) therefore remains unresolved. Regardless of their ultimate nature, ELDVs commonly provide comfort, and support psychological adaptation at life’s end. Clinicians thus have an ethical responsibility to recognize and validate these experiences within compassionate care.

As scientific understanding of the dying process continues to advance, the psychological and spiritual dimensions revealed through ELEs – particularly ELDVs – point toward dying as a potentially meaningful transition rather than mere cessation. More rigorous longitudinal research is needed to profoundly explore these phenomena and support a more holistic approach to end-of-life care.

If you work in palliative or hospice care and would like to learn more about the clinical management of ELDVs, we invite you to participate in an interactive online training. Access the training here: https://hospice-buffalo-9171.reach360.com/share/course/31c5bfbd-d9cb-4292-ba14-30b378d2bde7